Conceptualizing IHL: Levée en Masse & Perfidy

READ THE ORIGINAL ON THE CENTER FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES WEBSITE

Authors: PILPG and Weil, Gotshal & Manges

This blog post discusses two distinct legal concepts—perfidy and levée en masse. After examining the meaning of and relationship between the two, it is clear that these are complimentary concepts and that participation in a levée en masse is not a perfidious act. In addition, we note that in certain cases, Ukrainian civilians who participated in hostilities following the Russian invasion were entitled to combatant status as a result of a levée en masse and such participation, absent specific perfidious acts, did not constitute perfidy.

I. Levée en Masse

a) Definition

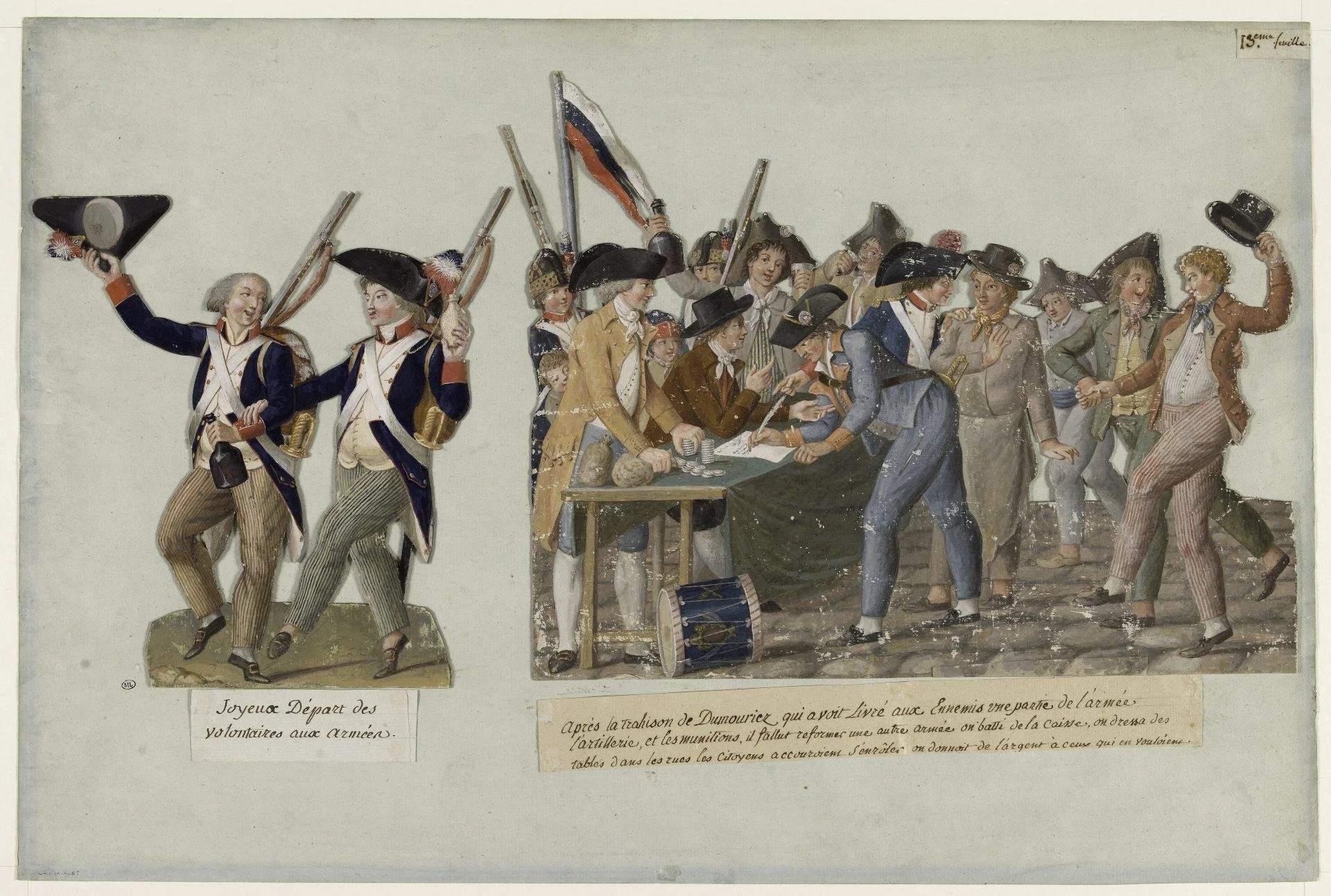

Long recognized as a historical concept dating back to the French Revolution, a levée en masse exists when inhabitants of a non-occupied territory, who on the approach of the enemy spontaneously take up arms to resistthe invading forces, without having had time to form themselves into regular armed units. These inhabitants are required to carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war. Though initially recognized in the Lieber Code (1863) and the Brussels Declaration (1874), Article 4 of the 1949 Third Geneva Convention codifies levée en masse as defined above.

b) Legal Consequences

Should a levée en masse exist, the participating civilians enjoy combatant status even when not part of regular armed forces or an organized militia. Combatant status provides participants with critical protections and immunities. For example, combatants are immune for prosecution for engaging in war-related hostilities, meaning that they may kill or wound enemy combatants in the course of an armed conflict so long as the individual did not engage in otherwise unlawful battlefield conduct. Conversely, a civilian participating in a levée en masse is entitled to Prisoner of War protections if captured, and as such, enjoy the protections outlined in the 1949 Third Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War.

c) Ukrainian and Russian Recognition

The concept of levée en masse is applicable to Russia and Ukraine through the Geneva Conventions and their own respective military manuals. Specifically, Russia provides that participants in a levée en masse enjoy Prisoner of War status upon capture and defines a levée en masse in nearly identical terms to the Geneva Conventions. Likewise, Ukraine’s International Humanitarian Law Manual (2004) states that Prisoner of War status is provided to, among others: inhabitants of a non-occupied territory, who on the approach of the enemy spontaneously take up arms to resist the invading forces, without having had time to form themselves into regular armed units (provided they carry arms openly and respect the rules of international humanitarian law). Therefore, both international law as well as Russia and Ukraine’s own military practice serve as the legal basis for the application of levée en masse.

d) Interpretive Challenges

The key issue in the context of the war in Ukraine will be whether and when did a levée en masse arise, and if one did exist, when it ended. Although the concept of levée en masse is widely recognized, there are few recent cases to analyze as there are no formally recognized instances of a levée en masse since World War II. To determine whether a levée en masse exists then, one must strictly interpret the definition. For example, regarding the concept’s temporal component, the Geneva Conventions’ Pictet Commentaries note that a “levée en masse may only exist for a brief amount of time. . . during the actual invasion period.” Once that period ends, the citizens must cease hostilities and either must join military forces or be replaced with lawful combatants. Moreover, to determine whether a levée en masse exists, one must answer the fact specific questions regarding whether the area is “occupied” or in the process of being invaded for the purposes of satisfying the definitional requirements under the Geneva Convention. Therefore, while these determinations are fact specific and open to interpretation, levée en masse circumstances arguably existed when Russia initially invaded Ukraine, but likely ended shortly thereafter.

II. Perfidy

a) Definition

Article 37 of Additional Protocol (I) to the Geneva Conventions outlaws perfidy as a war crime. The prohibition of perfidy provides that: “It is prohibited to kill, injure or capture an adversary by resort to perfidy. Acts inviting the confidence of an adversary to lead him to believe that he is entitled to, or is obliged to accord, protection under the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, with intent to betray that confidence, shall constitute perfidy.” Mere deceptive techniques, such as camouflage, decoys, and misinformation that do not otherwise violate international law do not constitute perfidy. Rather, perfidious activity includes feigning surrender, feigning incapacitation by wounds or sickness, or improperly engaging in activity to invite confidence with respect to an applicable legal protection. In essence, unlawful perfidy is a false, deliberate claimto legal protections under the rules of war to cause an enemy’s death, injury, or capture.

b) Source of Law

While outlawed under the Geneva Conventions, both Russia and Ukraine also recognize the prohibition of perfidy. Russia notes in its Military Manual that perfidy is a prohibited method of warfare, and its Regulations on the Application of International Humanitarian Law state that “[t]he prohibited methods of warfare include. . . resorting to perfidy.” Similarly, Ukraine’s International Humanitarian Law Manual states that perfidy, or deceit of an adversary by means of perfidy, is prohibited. Therefore, the Geneva Conventions, Russia, and Ukraine each recognize the prohibition of perfidy.

c) Legal Consequences

An individual who engages in perfidious activity in Ukraine would be in violation of both international and domestic law. As noted above, perfidy is prohibited under the Geneva Conventions. Moreover, Ukrainian Criminal Code provides for imprisonment for violations of binding international law of armed conflict. Therefore, any individuals engaged in perfidious acts in Ukraine could be subject to prosecution both internationally and domestically.

d) The Question in Ukraine

The key issue in Ukraine will be whether Ukrainian citizens who engaged in hostilities were committing perfidy, particularly by remaining in civilian clothing without military uniforms or distinct insignia or markings. To assess whether an individual is engaged in a perfidious activity, a citizen may not feign civilian non-combatant status and then engage in hostilities with enemy soldiers. But, as noted in the context of a levée en masse, civilians may receive combatant status if, among other requirements, those civilians carry arms openly. Therefore, while any inquiry would be fact specific, simply engaging in hostilities without wearing military uniforms or a distinct insignia as part of an organized militia is insufficient on its own to classify an act as perfidious.

III. Relationship Between Levee en Masse & Perfidy

In a scenario where a Ukrainian citizen engages in hostilities against Russian military members, the crucial question is whether such civilian acts provide for the protections of a levée en masse or constitute perfidy, or whether either concept is even applicable. The link between the two concepts is evident in this context—because perfidy is outlawed but participating in a levée en masse is protected, if an individual’s act fits the definition of one, it necessarily cannot fit the other.

Early codifications of both concepts provide insight to how the two concepts interrelate in this context. First, the Lieber Code and Brussels Declaration did not require the open carrying of arms in the definition of levée en masse, but did outlaw perfidy, meaning that the later “inclusion of open carriage of arms [in the Geneva Convention definition] was a logical extension of the requirement that regular armed forces not engage in perfidious acts.” [1] Therefore, if an individual fails to carry arms openly, that individual is not participating in the levée en masse, and could be subject to accusations of perfidy. Alternatively, if the individual does carry arms openly, and the other requirements for a levée en masse are present, then the individual will not have engaged in perfidious activity.

Moreover, when defining perfidy, the drafters of the Geneva Conventions struggled over the inclusion of one particular example directly relevant to levée en masse—feigning civilian status as codified in Article 37(1)(c). In response to several countries’ concerns, as well as advocacy for guerrilla combatants, drafters required that civilians carry arms openly (a requirement of levée en masse) to avoid the accusation of perfidy under a different section of Additional Protocol (I) to the Geneva Conventions. Therefore, the wearing of civilian clothes does not amount to perfidy if combatants fulfill conditions of legitimacy as set forth in Article 44(3), namely, open carrying of arms during military engagement and deploying preceding the attack.

In conclusion, a fact specific analysis would be necessary, but if a Ukrainian citizen is engaging in a lawful levée en masse pursuant to the Geneva Conventions, which would include openly carrying arms (but does not include any military identification), that individual enjoys the protections associated with participating in a levée en masse. Accordingly, while engaging in a lawful levée en masse, that individual did not engage in a perfidious act by remaining in civilian clothing.

[1] Emily Crawford, Tracing the Historical and Legal Development of the Levée en Masse in the Law of Armed Conflict, 19 J. Hist. Int’l. L. 329, 344 (2017).